PARTAGE

an exhibition on the separations and sutures of the colonial museum

FEBRUARY 18-25, 2023

ATELIER GALLERY

1301 N 30TH STREET

OPENING RECEPTION

FEBRUARY 18 | 6-9PM

about

Partage comes from the 19th to early 20th century archaeological practice of dividing collections and splitting objects in half between the host nation and the nation of the extractor, a premise that fractured histories and their representations. The artwork featured in this exhibition engages with themes of history and the way it is divided, the inequities of ownership, and new ways of imagining and communicating our past and future.

Partage is organized by Charlotte Williams, Chrislyn Laurie Laurore, Hakimah Abdul-Fattah, and Katleho Kano Shoro. The exhibition is supported by The Sachs Program for Arts Innovation, The Center for Experimental Ethnography, and Penn Cultural Heritage Center.

curatorial team

Alissa Roach

Borrowing from the compositional elements of 18th and 19th century nautical paintings, Voyager illustrates a journey without explicitly portraying water or ship. Rather, the focus lies on three central characters emerging from a web of symbols, each element sharing the color blue. Similarly to marine paintings, this dreamscape does not take place in a set location, but instead appears unanchored, floating without solid ground. I was interested in questioning the historical implications of voyage (imperialism, colonization, capitalism), and how water functions as the space in between national identity. In this “space-in-between” memory and identity become warped and blurry, left to dry in the wind and bleach in the sun.

Learn More

Candy Alexandra González

Candy Alexandra González is a Little Havana-born and raised, Philadelphia-based, multidisciplinary visual artist, poet, activist and trauma-informed art educator. Candy received their MFA in Book Arts + Printmaking from the University of the Arts in 2017. Since graduating, they have been a 40th Street Artist-in-Residence in West Philadelphia, a West Bay View Fellow at Dieu Donné in Brooklyn, NY, Leeway Art and Change Grant Recipient and the 2021 Linda Lee Alter Fellow for the DaVinci Art Alliance. Candy is currently an Art + Art Education doctoral student at Teachers College, Columbia University.

Learn More

Destiny Crockett

Destiny Crockett (she/her) is an analog collage artist. Specifically, she is inspired by African American sartorial elegance of the mid-to-late 20th century through today, especially as it relates to African American childhoods. She is originally from St. Louis, and currently lives in Philadelphia. She is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Pennsylvania, where she focuses on Black feminist theory and African American literature and visual arts of the 20th century.

Irwin Freeman

Fresco, intimate scale: allegories in peeled-away layers of the home that personal liberty, granted us or rescinded, will occupy.

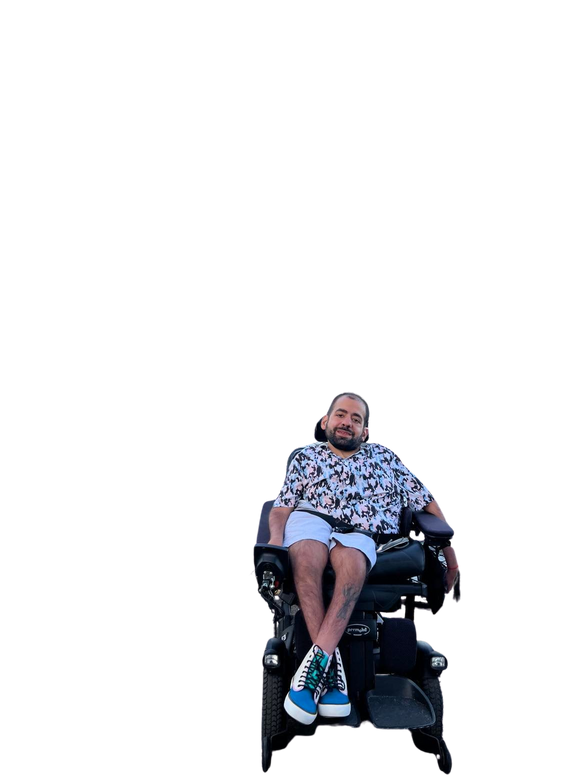

Jaggar DeMarco

Jaggar DeMarco is a second-year media and communication Ph.D. student at Temple University’s Klein College of Media and Communication. He works as both an interdisciplinary scholar and media maker. As a scholar, his research explores the intersections of disability arts, culture, and politics. His work examines media created by and for disabled people and explores how this media differs from media that is typically meant to “represent” or “speak for'' the community. As a media maker, he is dedicated to excavating disabled and crip lives to illuminate their poetic and creative potential in the face of oppressive systems. His life as a self-identifying disabled individual and disability justice activist is never far removed from any of his work, and in fact is central to his planned future research and creative endeavors. All of his work is grounded in an intersectional framework that draws upon the cross-section of race, gender, sexuality, and class, which define the learned knowledge of disabled individuals.

Julia Mallory

I am a storyteller whose work manifests through a variety of mediums, from text to textiles. My Cape is Hanging Somewhere in a Museum series is based on capes I created that are embodied through photography, and tell stories about Black folks' relationship to labor, leisure, and loss. My first collection of poetry was completed on the heels of my first bout of burnout. This collection, my first formal archive of survivorship, would prove instrumental as a healing resource after the death of my eldest son a few months later. Loss or what no longer exists in its original shape or form, was the catalyst for me to understand the care that I needed as well understand the care I have offered over the course of my life. I never had an interest in being a StrongBlackWoman but that generational inheritance had already been secured, the cape, essentially functioning as a heirloom that I had been fit for, and expected to put on. The epigraph in my first book read: “For every time my cape almost became a noose.” With this series, I am thinking through the museum as a multipurpose site that collects, makes visible, and retires or shifts objects from their original purpose. I am asking viewers to engage with their own relationship to labor, leisure, and loss. Including what would be a suitable site for such a museum for them and what other artifacts of their personal archive, along with the location of “somewhere” within the space.

Kita Rich

As a Black child and still, in my adulthood, I am constantly told not to take up space within our community and public spaces. Strange gawking eyes at the art galleries, being followed around a boutique, and or being questioned why I am in this neck of the woods. Ask any Black person living in America if they have experienced something of the sort in addition to the feeling of not being allowed to just exist. However, the spaces we are socially “allowed” to occupy are labeled “urban” and “hood” in contrast to our white counterparts trying to live in these areas they are then labeled “hip” and “up and coming”. As if we do not belong in the places we helped create, socially, economically, and historically.

The goal of my art is to reclaim spaces that have historically belonged to marginalized communities for generations, through place-making and hidden public art. My art consists of walking through, learning, and interacting with the people and landscapes I photograph and eventually collage. These collages will later be printed into stickers and hidden within the site. So the next time that person returns to that site they see themselves within the landscape.

My work focuses on recentering the conversation on the voices that have been left out of history. This would nestle into the topic of this exhibition of recontextualizing artifacts throughout history. History is written by the oppressor, this is our chance to speak our truth and display our experience of history.

Mel Brown

Mel Brown is a transdisciplinary artist who disrupts temporality through performances of redacted (a)historical narrative. Brown’s scope of work employs site specific research, lens-based media, and modern-day relic making. Brown received a B.A. in Integrative Art from Pennsylvania State University in 2012 and is currently a dual degree master’s candidate at Weitzman School of Design and School of Social Policy & Practice.

My work anticipates the material documentation of a collective temporal unsettledness, against the peripatetic unsettledness of my own life. When are we when the future is already an ancient environmental ruin? Agamben describes the contemporary as people “who truly belong to their time [...] who neither perfectly coincide with it nor adjust themselves to its demands.” It is this unstable condition that makes the contemporary “more capable than others of perceiving and grasping their own time.” Like Klee’s angel, we are caught in the incongruency of time, “on time for an appointment one cannot help but miss.”

As an artist, I have set out to examine the untimeliness of contemporary life. I borrow archaeology as a method with which to enter the present and the future. I don’t work as an archaeologist but as forger of a proleptic archaeological record composed of artifacts, traces, and tools produced for interpretation. Using ceramics, I cite the past and present, invoke the future, and dress fictions in the cloak of history. The record I am forging is for me to perceive my time–its disconnection and anachronism–by materializing a future in which the contemporary will have been available and examined: archaic vessels that will have contained the pigmentary remains of a current invasive species; measuring sticks forgotten at various sites that will have been interpreted as sacrificial offerings. These objects mix references from different cultures, times, and locations, touching on the blurring of distinctions between the sacred and profane by museum displays, and in resonance with my life experience.

Paolo Mentasti

Peri Law

My work appropriates from my multiracial heritage, recreating domestic scenes and revising objects to reflect the global imperialism that soaks my bloodline. I transform home and vessels to have an element of control over my family history and to create my own meaning. There were no objects passed through the generations in my family; they are all lost to time and war, and the stories that are shared are losing their edges. I lean on print so I can give tangibility to these memories and produce multiple copies in the hopes that if one is lost, there are several more that can continue on. The David Vases in the British Museum have appeared frequently in my work since 2019 when I first viewed them in the flesh, as I see them as a reflection of my own colonized existence. The displaced Chinese vessels were sent to the epitome of the institution in my patriarchal homeland. I find it fascinating how their identity has been reduced to the name of the owner, Sir Percival David, lacking any connection to the real reason as to why they are so famous. I further manipulate the famed vessels in my work, recontextualizing them with personal inscriptions, placing them in fictionalized retellings of my family history, and breaking them. My art is heavily influenced by the art historical canon, imagining traditional Asian art through the lens of the contemporary diaspora, existing with apathy, an over desire for connection with others, and a longing for self-acceptance.

Shwarga Bhattacharjee

My current work generates from the duality of experiences as an immigrant. On one side, I am going through a seemingly never-ending phase of adaptation to the new societal and political culture in the United States. On the other side, I am engaged in a continuous introspection into my origin, which has driven me to delve deeper into my South Asian heritage. My work is a search for my identity within the simultaneous experience of colonial and post-colonial cultures. I was born into it and struggled through it my entire life. I use layers as the physical expression of my thoughts. My approach and techniques have varied, but the search for identity has been a constant.

Susie Callista Suh

My artwork is the exploration of the Asian American diaspora from my perspective as a Korean American woman. I choose this theme as meditation on my father’s death and to confront my struggles with depression. I organize my body of work into chapters which are: my personal experiences, Korean American history, and my family’s past in Korea. As for the style of my work, I reference: minimalism, contour drawing, and literary vignettes. My art mediums are primarily silk thread, muslin fabric, and paint. Each artwork represents a tangible memory and come in the forms of sewn text, sewn drawings, and sculpture. I use sewing as a method to access core memories, the needle is used to penetrate the surface of the fabric, which represents the ego. The art making process is slow and forces me to take the time to reflect on my internalized memories and experiences. I depict my experiences using a contour drawing style with the thread and I use a limited color palette to abstract the images. This allows me to tell a story by its most basic components: form and color. The physical form of the artwork is significant because it is indicative of my relationship to the memory. Memories that were experienced firsthand are conveyed three dimensionally, whereas distant memories or historical events are portrayed as flat sewn drawings. My goal as an artist is to provide an authentic perspective on the Asian American experience, to empathize and support the experiences of other marginalized people.

Tania Qurashi

My work is rooted in my identity as the daughter of immigrants from Pakistan and Guatemala. Through paintings and drawings, I explore the cultural, racial, and ethnic melancholy and isolation. Gardens, windows, fences, and objects respond to the many facets of my identity as a child of immigrants, a multiracial and multiethnic woman, subjected to American history and idealism. Objects become vessels of exchange between cultures and generations, as well as channels to explore the romantic, religious, personal, and the political. The distance between the object and the flower relate to the distance between nations of origin and its diaspora. By extracting flowers from the garden and placing them within foreign vessels, the paintings become portraits of homelands that are both rooted and uprooted. The garden becomes the location for the search of self and a place where intersections between cultures, histories, and identities can exist and grow without rejection or uncertainty.

In Obscuro, the national flower of Guatemala is placed within a vessel from Pakistan. I reimagine instances where these two cultures, histories, and identities collide in the painting and whether their origin is recognized by others. The paintings of objects challenge our assumptions of people, objects, and geographies presented in museum spaces.